So you’re starting a React project. You know what you want to build, and quickly spin up a project with create-react-app. And then you’re confronted with the problem of where.

Where do your components go? Where should you put business logic? Where do higher order components fit in? And even if your structure feels right now, how do you know that it won’t feel wrong later?

If you’ve used other frameworks, you know that it doesn’t have to be this way. Rails gives you structure. So does Angular. What if React also had a system that told you exactly where files go? You could focus on building stuff instead of dicking around with folder structures.

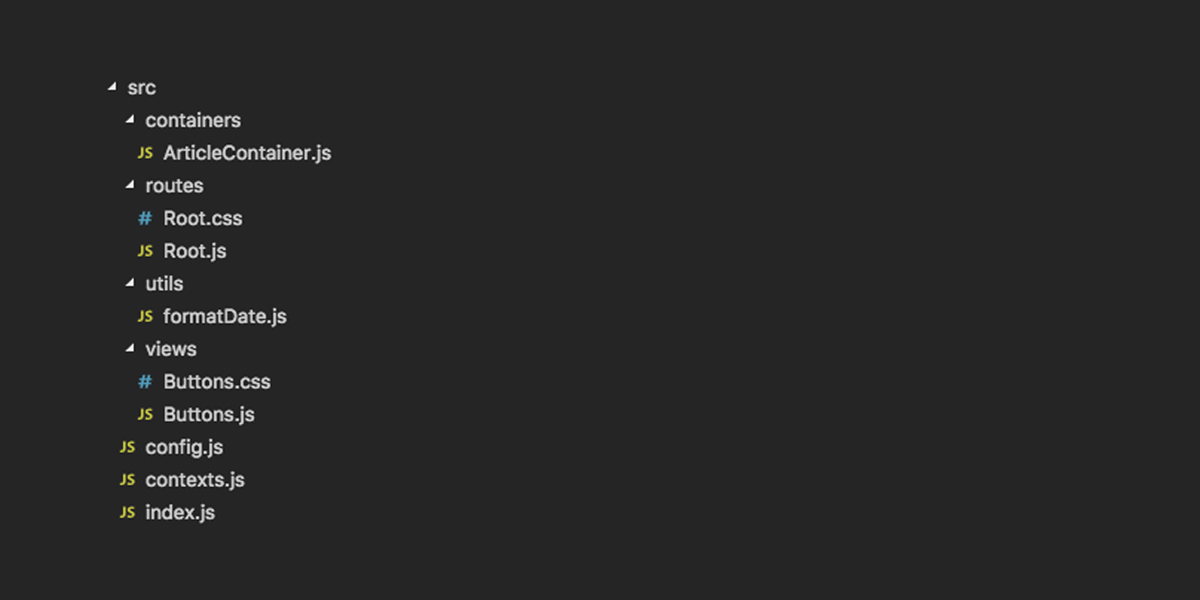

In fact, there is a system that does just this. I’ve been using it for months now. It works great with create-react-app and any router you pick — even no router! And it’s named CRUV, after the 4 directories that you’ll use.

Containers, Routes, Utils, Views

CRUV is inspired by the directory structure from Ruby on Rails. It gives you four standard directories, for the things that you’ll definitely use. Then it lets you add other app-specific folders and subdirectories once you need them.

Creating a CRUV app is simple. All you do is generate an app with create-react-app, and then create 4 folders and 2 files. You can try it out by copying and pasting this into your terminal:

create-react-app myapp

cd myapp/src

mkdir containers routes utils views

touch config.js contexts.js

mv App.* routes

sed -i '' -e 's/.\/App/.\/routes\/App/g' index.js

But what do the 4 directories and 2 files in this structure actually do? Let me demonstrate with examples from the app that runs my new Raw React course. Shameless plug: join my newsletter at the bottom of this page to keep in the loop when the course is released, and get a massive discount.

/containers

This directory contains reusable container components. These components handle business logic, delegate style/markup to view components, and importantly, are used in more than one place.

Container components can also communicate with the server. In larger apps, they may delegate this to a Redux or Apollo store. But in smaller apps, they’ll usually just call the server directly.

Examples include:

- An

<ArticleContainer />component that loads and wraps MDX documents. - A

<CourseLessonContainer />component that loads course access/progress from the server, and handles user requests to mark lessons as complete. - An

<EditorContainer />component that handles loading/saving of the students’s answers for exercises.

But what if you have something that looks like a container, but is only used once? Then it probably goes in /routes.

/routes

Routes are general purpose components that are only used once. They can handle both business logic and presentation internally, or they can delegate it to containers or presentation components.

Routes often correspond to individual URLs, and that’s where they get their name. But routes can also be independent of URL.

Examples include:

- An

<App />component that wraps everything else, renders the app header, and decides what to render based on the current URL. - A

<LandingPage />component that contains your landing page’s content. - A

<LoginPage />component that shows a login form, and handles user input on that form.

So what router should your routes use? Whichever router you’d like, or even none at all! Because even if your app runs from a single URL, you’ll still need an <App> component. Maybe you’ll have other one-off components too.

/utils

This is the place to put files that get copied and pasted between many different projects. Things like vanilla JavaScript functions and classes, higher order components, and other utilities.

Some examples include:

- A

formatDate()function that converts JavaScriptDateobjects into strings. - A

<Dimensions>component that uses a render prop to make thewidthandheightof its children available.

/views

Put components that render markup and styles here, along with components that receive and display user input. Dan Abramov calls them presentational components. I call them “views”, because it’s faster to type within import statements..

Some examples:

- Styled

<Button>components. - A

<CourseCard>component that creates a link to a given page, and looks like a “card”. - A

<Grid>component that is used within route components and other views to handle layout.

I tend to start by creating one .js, .css and .test.js file per component, and putting them directly in the /views directory. So for example, /views/Button.css, /views/Button.js, and /views/Button.test.js. But this isn’t a hard and fast rule; you can also export multiple components from a single file. For example, an Indicators.js file may export both <Spinner /> and <LoadingBar />.

/config.js

Apps often have configuration that differs depending on the environment. For example, an API_KEY environment variable that differs between development, staging and production. While you can access this kind of configuration directly from process.env, I prefer to export it from a top-level config.js file. For example:

export default {

server: process.env.REACT_APP_SERVER || 'http://localhost:3000',

publicURL: process.env.PUBLIC_URL,

stripeKey: process.env.REACT_APP_STRIPE_KEY,

}

/contexts.js

To use React’s Context API, you’ll frequently need to import <Context.Consumer /> components, which often don’t fit in any of the other categories. I like to keep these components in a single top-level file, making them easy to access, and also discouraging over-use of context. Here’s an example:

import * as React from 'react'

// Current route and methods for interacting with browser history

export const NavContext = React.createContext(undefined)

// Data received from server

export const StoreContext = React.createContext(undefined)

// UI context, including whether the subtree is disabled, is a form, etc.

export const UIContext = React.createContext(undefined)

/index.js

This is your application’s entry point, as created by create-react-app! Simple, huh?

As your project grows…

As your project grows, your views and routes folders can start to feel a little full. In this case, you might want to add subdirectories for each component, with an extra index.js file that re-exports the components. This let’s you keep the same filenames as before, without having to change any import statements.

For example, a /views/Button/index.js file might look like this:

export * from './Button.js'

You may also find yourself adding subdirectories that group related components. For example, I have a /views/editor subdirectory that groups together all the components involved in my course’s live editor.

Finally, in addition to the standard four CRUV directories, you may also find other useful directories. For example, my app has a /types directory, because it’s written in TypeScript. But I didn’t start with this directory. I only added it once my /utils directory got a little heavy with type definitions.

The reason that the CRUV structure works is that it’s just a starting point. When you’re just starting out, it gives you a simple structure to work with so that you can concentrate on writing actual code. And once your folders get full, all you need to do is find a few similar files, and move them into a new directory. It’s easier to categories files that already exist than to predict the future.

But where do my reducers go?

You may noticed that I haven’t added a directory for Redux reducers. And that brings me to this article by one of the creators of Redux: You Might Not Need Redux. Yes, you read that correctly: one of the creators of Redux is asking you to reconsider using Redux.

The reason that there are no /reducers or /actions directories in the CRUV structure is that Redux is optional. In fact, I write apps without Redux all the time!

But what if you do use Redux? Or MobX? Or Govern? In that case, my recommendation is that you add a /store directory, and put all your store related code in there. Stores hold global state that isn’t tied to a specific component, so they generally shouldn’t be very large.

And if you do have state that needs to be tied to a specific component? Use setState()! That’s what it is there for; component state is a simple, powerful, and underappreciated tool. Raw React can get you a long way.

Where is CRUV used?

If you’ve worked with some React apps before, CRUV may feel familiar. While the names are probably a little different, this pattern is something that often evolves by itself — especially when building on the Presentational and Container Components pattern.

In my case, CRUV is the structure that evolved from an app that I’m building to teach Raw React. I’ll be going into more details on how I built the platform behind the course soon. To get the details, or to be the first to hear about the Raw React course (and get a massive discount), join my newsletter below! I’ll even email you five free PDF cheatsheets to sweeten the deal.

I will send you useful articles, cheatsheets and code.

One more thing – I love hearing your questions, offers and opinions. If you have something to say, leave a comment or send me an e-mail at james@jamesknelson.com. I’m looking forward to hearing from you!